- Lynda Barry, the cartoonist who became an unlikely guru for finding your creative selfhood no matter whether you're destined for "high art"

- The stunning work of Ayako Tani, whose medium of choice will make you do a double take

- Links to thoughtful stories from around the web on Russian artists against the war, New Year's resolutions for writers, the power of domesticity and more

- Grants, fellowships, prizes, job opportunities and more in creative disciplines and organizations

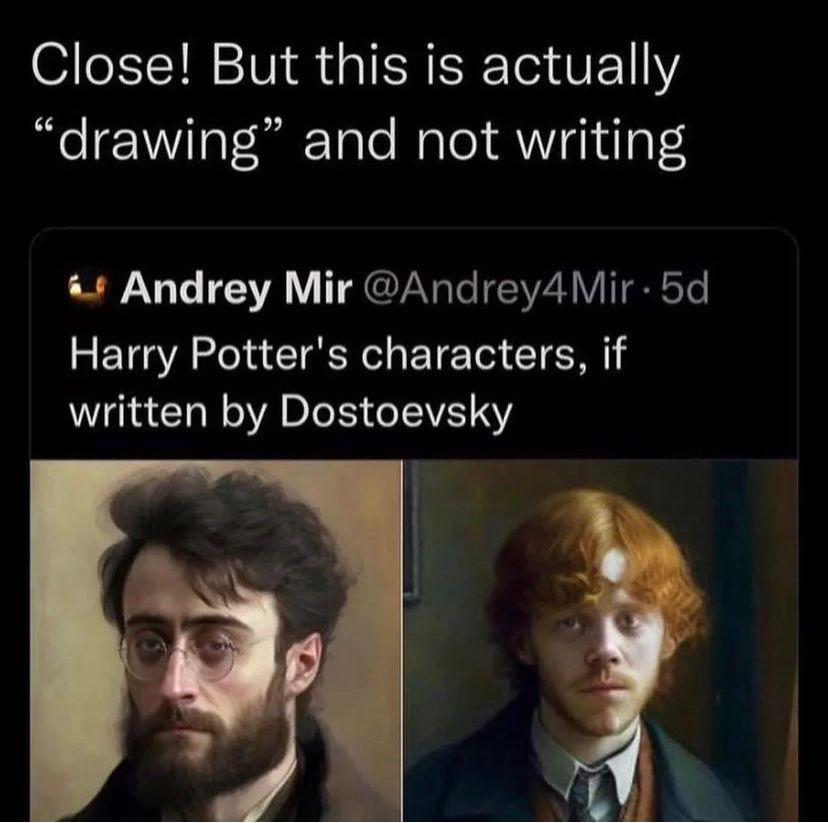

- What would Voldemort look like if he was written by Dostoyevsky

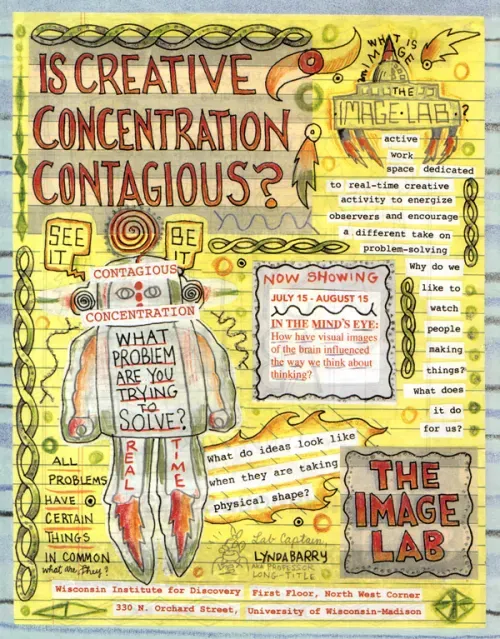

Creative roadmaps

The 90s cartoonist bringing creative transformation to bartenders, janitors and hairdressers, and you

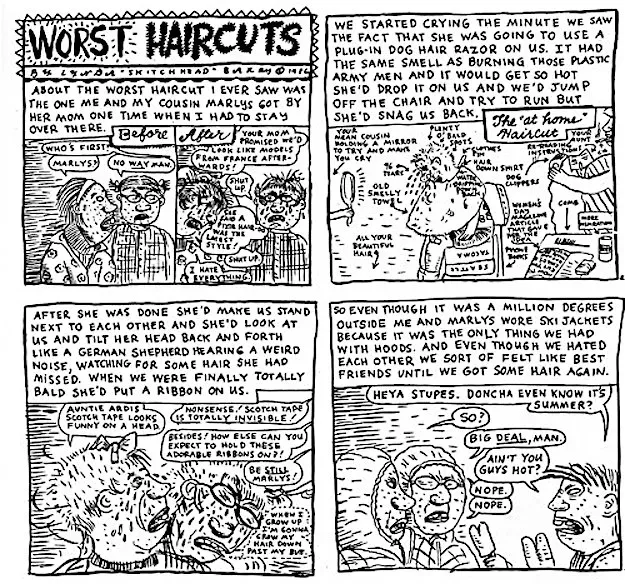

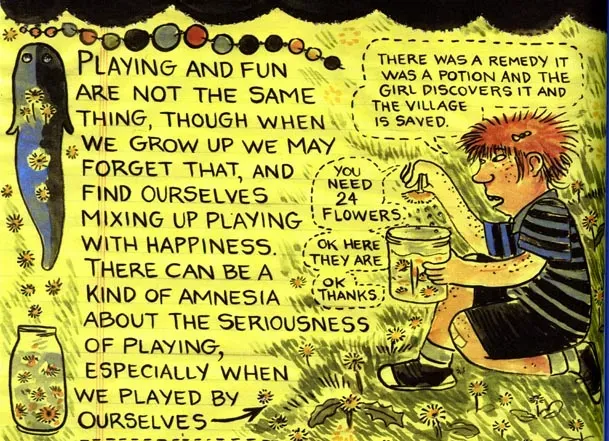

Lynda Barry has gone by several names — born Linda Jean, she changed her name to Lynda at age 12, the same year she dropped acid for the first time. Her minimal web presence is called “the nearsighted monkey,” and in her capacity as a teacher in her writing and creativity workshop, she goes by “Professor Skull.” (Actually, everyone is given a new name for the duration of her class; each cohort of students is granted their new name at the beginning of the course.)

In all her different avatars, Barry is an unstoppable force of creative power, and one who notably refuses to recognize distinctions between “high” and “low” art, or even what constitutes “real art” at all. Barry began her career as a cartoonist, with cult favorite comic strip “Ernie Pook’s Comeek.” Her work chooses to depict things as they are (or even a little uglier than they are) rather than as they “should” be — visually, it’s busy and brash, and unconcerned with delicacy or traditional beauty. Her characters have zits and bad hair; they argue and have outbursts, and sometimes live in a trailer park. They don’t seem that unlike Barry herself at points in her life, who grew up as the child of working-class parents and was working nights as a janitor in high school, and whose parents thought it was a waste of time for her to go to college or pursue art.

Although Barry isn’t interested in the cult of trauma porn, she’s clear about the role art and the making of it have played in moving through some of the difficult circumstances she grew up in. There’s a story she tells in her classes about “Family Circle,” the long-running comic strip in newspapers across America:

"’I grew up in a house that had a whole lot of trouble,’ she said. “As much trouble as you could imagine. In the daily paper, there were all these comic strips, and there was one that was a circle. It seemed like things were pretty good on the other side of the circle. No one’s getting hit. No one’s yelling.”

Once, at a comics convention, she shook hands with Bil Keane’s son, Jeff — Jeffy — who now inks the strip. Barry instantly burst into tears. She told the class why: ‘Because when he put his hand out and I touched it, I realized I had stepped through the circle. I was on the other side of the circle, the place where I wanted to be. And how I got there was I drew a picture.’ She smiled and held her arms out. ‘The reason I’m standing here… is because I drew a picture and wrote some words.’"

Barry’s classes have become something of a monument to this fact, and to her belief that anyone can draw a picture and write some words. Her classes are marketed specifically to “non-writers” — “THIS CLASS WORKS ESPECIALLY WELL FOR ‘NONWRITERS’ like bartenders, janitors, office workers, hairdressers, musicians and ANYONE who has given up on ‘being a writer’ but still wonders what it might be like to write.”

The coursework doesn’t focus on beginning writing exercises, grammar or narrative lessons — most of it doesn’t look much like writing at all from the outside. Students might make lists, draw spirals, draw an X across the page and fill each quadrant with something different. In her attendant cartooning class, Barry has students draw Batman over and over again. The point isn’t to learn specific skills associated with drawing or writing; the point is to learn about building your own creative process, accessing that precarious spirit of play and experimentation that you can’t create real art without no matter how technically proficient you are.

“'Kids don’t plan to play,' she told her class in the first day. 'They don’t go: ‘Barbie, Ken, you ready to play? It’s gonna be a three-act.’' Narrative, Barry believes, is so hard-wired into human beings that creativity can come as naturally to adults as it does to children. They need only to access the deep part of the brain that controls that storytelling instinct. Barry calls that state of mind “the image world” and feels it’s as central to a person’s well-being as the immune system.

'Somebody said to me one time, ‘This class is like therapy,’ ' Barry said. She shook her head. 'No. Therapy is like this. And this is very old.'"

Although Barry’s classes are taught in person and not widely accessible, she’s recorded some of her wisdom in books like What It Is and Syllabus, texts aimed at capturing some of her process and philosophy in beautifully illustrated form. She also maintains a free public Youtube account where she documents some of her core exercises, like the spiral she has students draw as a ritual to ease into working.

Although Barry is a contemporary of plenty of commercially successful artists like Matt Groening, creator of the Simpsons (and is certainly successful herself, with highly lauded published books of her work), she’s a unique figure in the arts world: not only has she carved out a place for herself despite starting out from well outside the circles of high art, but she’s carved a path backwards from there to allow others to follow her and learn from what she’s experienced. In her classes, Barry tells the story of a neuroscientist working with patients experiencing “phantom limbs,” and a patient who suffers the constant discomfort of feeling his phantom hand always balled into a fist he can’t unclench.

"The only way to open that fist, she said, is to see your own trouble reflected in an image, as the patient saw his hand reflected in a mirror. It might be a story you write, or a book you read, or a song that means the world to you. ‘And then?’ She opened her hand and waved.”

| Tell friends about us → win prizes | |||

| 2 Referrals Hero's Circle Infographics | 10 Referrals Week of Creative Warm-ups | 25 Referrals Early Access to the Narrative therapy platform | |

| Check your referrals | |||

| Powered by Viral Loops | |||

Creative Soundbites

🖌️ Tschabalala Self’s painted women find power in domesticity

🍾 New Year's resolutions for writers that aren't about writing

🕊️ Read about the anti-war street artists still working inside Russia

🎨 A profile of "maverick painter" Henry Taylor

📚 Two novelists in conversation about their "mutual obsession with art in all its forms"

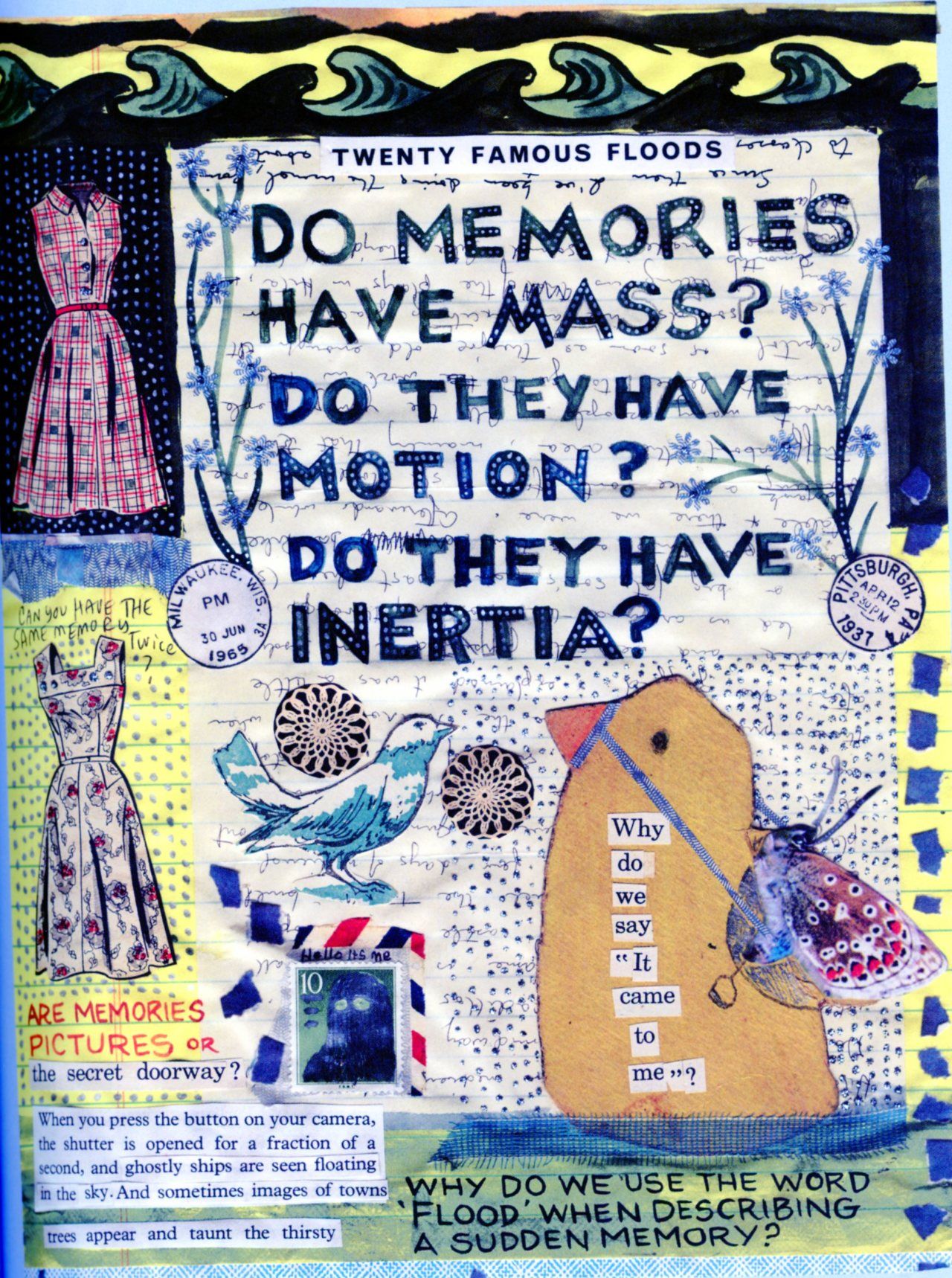

Visual of the Week

Ayako Tani is a glassworker and researcher of glass who studies lampworking techniques to make her art. While some of her work includes forms we might normally associate with glass, like ships in a bottle, she also pushes the envelope of what's possible with the material like her "Ghost" series, which draws from calligraphy.

Opportunities

+ Showcase, a literary publication whose issues each focus on one object and one idea, is accepting submissions for flash prose and poetry.

+ Chicken & Egg Pictures, which supports women filmmakers, is looking for a senior program manager.

+ Hedgebrook's Writer-in-Residence program, which offers women writers two- to four-week residency stays, will open for applications on February 15.

Meme of the week

Today's newsletter is brought to you by Rachel Kincaid, Alyona Belyakova, and Egor Mostovshikov