Wish you knew how Toni Morrison wrote The Bluest Eye and other masterpieces? Anyone near Princeton, NJ, is in luck on that one – the university will be showing an extensive exhibit on her creative process and her archives, opening on February 22.

"'As writers we often want to get to the finished product and know that we have cracked the code,' [curator Autumn Womack] said. 'But you see (Morrison) trying and over and over and over and over again, asking questions, looking at different objects, trying different research methods, trying different narrative voices.'"

In this issue of The Order:

- James Pennebaker's research in the 1980s showed writing about our emotions can do things we never thought possible — here's how you can use his findings now

- The Gifts of Trauma and the work The Order has been doing with clinical arts therapist Kit Loring

- The textile work of Tabitha Arnold, creating stunning tapestries of our most complex communal moments

- Links to stories about David Byrne's creative hack, a new app for brainstorming and collaboration, NYC's creative spirit, and more

- Grants, fellowships, prizes, job opportunities and more in creative disciplines and organizations

- We're launching the referral program, yay!

Writing to heal

James Pennebaker's expressive writing paradigm

For decades, scientists — like the rest of us — have struggled with a difficult conundrum. Emotional and psychological harm can be incurred anywhere, almost instantaneously, and is widespread; meanwhile, the best practices for addressing it, like comprehensive therapy and deep social connections, take a very long time and are inaccessible to many. That’s why it caught social psychologists James Pennebaker’s attention when he noticed a surprising side effect of polygraph tests (yes, the lie detectors they use on procedural TV shows):

James Pennebaker had been invited to give a series of talks to top-level polygraphers working for the FBI and CIA. In late-night conversations following the events, these experts captured Pennebaker’s interest with similar stories. A bank vice-president, for example, showed intense physiological stress while being questioned. When he broke down and confessed to embezzlement, however, he became extraordinarily relaxed. Many polygraphers had made the same observation – even while facing severe consequences, individuals felt liberated after confessing their actions.

Based on this, in the 80s Pennebaker developed a line of research and inquiry that explored what happens when we keep important, meaningful or shameful things inside; his research revealed that “people who experienced trauma and kept it secret were most likely to have health problems.”

It followed, he thought, that if keeping trauma secret caused health problems, that sharing them would improve health. He needed to find a way to make sure that sharing these secrets was safe and accessible for his research subjects, and not causing further harm by having them unload their deepest shame to an indifferent researcher, so he decided to explore having them write it down.

In a controlled study, Pennebaker had one group of people. the control, write about low-stakes, superficial issues in their lives for 15 minutes a day. To the other group, he gave the following instruction:

For the next four days, I would like you to write your very deepest thoughts and feelings about the most traumatic experience of your entire life, or an extremely important emotional issue. You might tie your topic to other parts of your life: your childhood, your relationships with others, your past, present or future. All of your writing is confidential. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar or sentence structure. The only rule is that once you begin writing, you continue until the time is up.

The anecdotal responses to this prompt were immediate, with research subjects reporting in the moment that the process had been profoundly impactful for them. Maybe even more significant, though, were the findings that Pennebaker made about this group in the weeks after the study. He found that the group that shared their deepest feelings in writing had decreased anxiety, depression, blood pressure, stress and pain; reported better sleep and memory, had better immune function, and even increased grades and work performance. Many of the quality of life and health indicators that are tied to depression and/or to complex trauma were noticeably improved, outcomes we’d often expect to see after weeks or months of talk therapy, after only four days of writing. In a similar study of Holocaust survivors, Pennebaker found that those who disclosed more about their feelings and experiences were significantly healthier a year later than those with low levels of disclosure. Based on this, Pennebaker developed his “written emotional disclosure paradigm:” that “written emotional disclosure improves physical and psychological health.”

The implications of this work were major; while therapy can be expensive, time-consuming, and inaccessible to many, a notebook and regular writing are accessible to almost all of us. Pennebaker’s findings meant that many of us may have more agency and control over our wellbeing, and our ability to heal from some of the worst things that have ever happened to us, than we could have imagined.

In the 2000s, Pennebaker shifted his research to focus on the impact of expressive writing on social relationships. He found that people who wrote about their relationships experienced an improvement in their relationships with others. He also discovered that expressive writing can help people express their emotions in their relationships and lead to better communication and understanding.

Pennebaker also conducted research on how expressive writing can be used to improve creativity and problem-solving. He found that people who wrote about their creative ideas experienced an increase in their creative output and their ability to come up with new ideas.

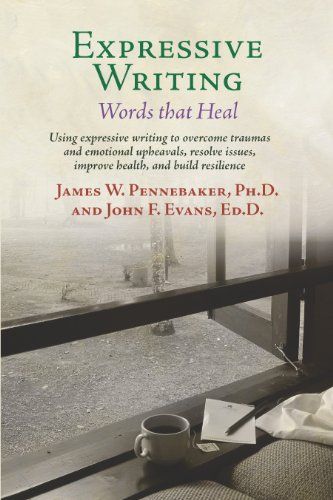

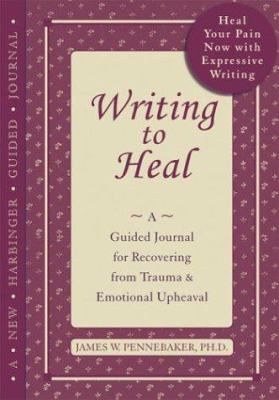

Pennebaker’s work in expressive writing has empowered many people — while critics say that the boosts in wellness people see from expressive writing are relatively small, Pennebaker points out that they’re proportional to many of the outcomes we see from established medical treatments. Pennebaker has also created a series of books designed to help people access the benefits of expressive writing on their own; enabling them to “be their own therapist,” as it were.

The Gifts of Trauma

Not coincidentally, Pennebaker's findings about the power of writing in the face of trauma are things we've noticed, too, and are working on putting into practice for our community. We've been running a therapy class for Ukrainian and Russian members in the wake of the ongoing harm of the war, led by UK psychologist and psychotherapist Kit Loring. Certified British Clinical Arts Therapist, clinical supervisor and trainer, member of the British Association of Drama Therapists, co-founder and co-director of the humanitarian art therapy organization Ragamuffin International, he believes that the use of the Arts, in all their forms, proves to be an empowering and deeply moving cathartic experience in the process of healing trauma and the multiple symptoms associated with it.

Much like Pennebaker calls for, workshop participants find that opening up and working through difficult feelings in a supportive space has impacts far beyond the workshop setting itself. "Kit and the curators create a safe space in which it is not scary to open up and be heard. Even the fact that we are at a distance does not prevent me from feeling the emotional warmth between people," wrote Hanna S, a workshop participant from this session. "I think that I would recommend this course to those who want to look inside themselves through the prism of creativity and start working with deep feelings using the tools of words, colors and images."

We'll soon be launching a companion program with Kit for US members, so watch this space for updates! You can also be entered into a drawing for early access to our platform and more resources like this by sharing The Order with friends!

| Tell friends about us → Win prizes | |||

| 2 Referrals Hero's Circle Infographics | 10 Referrals Week of Creative Warm-ups | 25 Referrals Early Access to the Narrative therapy platform | |

| Check your referrals | |||

| Powered by Viral Loops | |||

Creative soundbites

⏲️ A virtual workshop on planning your time by creative copywriter Ilaria Mangiardi.

🎶 David Byrne's process of "little beginnings" to create incredible art.

🧵 On the art of creative mending, making torn clothes look not like new, but more beautiful.

🏙️ Did New York's creative spirit revive during the pandemic?

📱 A new app designed for creative brainstorming and collaboration.

Visual of the Week

Tabitha Arnold is a textile artist who first studied painting before teaching herself the laborious process of punch needle embroidery. She's "inspired by the history of the labor movement, as well as her own direct experiences as a worker, organizer and artist coming of age during a wave of unionization and class-consciousness." From Hyperallergic:

"Arnold’s textiles are populist and devotional, projecting scenes of collective outrage into transcendence. To her, fiber art can convey a sense of familiarity while inviting groups of disparate viewers into conversation about widespread inequality and abuses of power. This is a philosophy exhibited by Mexican muralists and Soviet mosaic artists, but that also manifests in Afghan war rugs and the quilts of Gee’s Bend. Arnold invites these influences into conversation as well, laying the groundwork for new connections between art and organizing."

Opportunities

+ Applications for the London Emerging Writers program will open on January 11, 2023.

+ Bay City, MI will be hosting its 100 Day Project, "a challenge where artists and creatives are asked to spend time each day for 100 days on making art."

+ The Recurse Center is accepting applications on a rolling basis for its educational residency, which is for "anyone who wants to get dramatically better at programming."

+ Sculptor Arlene Schechet is seeking a manager/administrator for her studio.

+ Courage to Write grants are offering seven grants of $7,000 each in the spring of 2023, in addition to three grants dedicated to writers working on projects about immigration/refugee issues. Up to ten additional writers will receive grants of $1500 each.

Meme of the week

| Tell friends about us → Win prizes | |||

| 2 Referrals Hero's Circle Infographics | 10 Referrals Week of Creative Warm-ups | 25 Referrals Early Access to the Narrative therapy platform | |

| Check your referrals | |||

| Powered by Viral Loops | |||

Today's newsletter is brought to you by Rachel Kincaid, Alyona Belyakova, and Egor Mostovshikov